The Harvest: This Week in Rural China – Dispatch No. 21 (20 November 2025)

Confucius Institutes go agrarian, Qinghai goes organic, and one village doctor does the work policy can’t.

It’s been a while since the last edition of The Harvest. Rather than force it, I stepped back for a while. Silence wasn’t the intention, but it happens—especially when you name a project This Week in Rural China and then try to keep pace with it.

Still, I’ve missed writing this, and many of you have written, nudged, or simply stayed subscribed. To those who kept paid memberships running during the hiatus: thank you. As a gesture of appreciation, all existing paid subscribers are now lifetime founding members. Paid memberships reopen from this dispatch onward, but nobody who supported this project early on will ever pay again.

My aim is still to publish weekly. That rhythm remains the heartbeat of The Harvest. But authenticity matters, and there will be weeks where the schedule stretches. I’d rather write steadily and well than chase the calendar for the sake of it.

For new readers: The Harvest gathers stories from China’s rural regions—policy shifts, demographic trends, environmental pressures, and the human stories that rarely reach international coverage. For more, see Why Rural China Matters.

As always, I welcome your thoughts. Your comments and emails shape these dispatches as much as the stories themselves.

Now, let’s pick things up again, This Week in Rural China:

Confucius Institutes Turn to Agricultural Partnerships

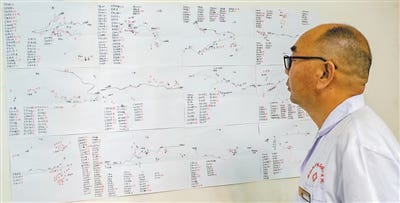

Hand-drawn health maps: one village doctor’s attempts at reform

Modernising state-owned forest farms: policy from 2030 and 2035

Qinghai rolls out full-coverage organic grassland monitoring

Guangdong’s late rice harvest shows mechanisation at work

Confucius Institutes Head for the Fields

At the World Chinese Language Conference this month, officials unveiled a new Global Alliance of Agriculture-featured Confucius Institutes (全球农业特色孔子学院联盟). According to the announcement, 510 Confucius Institutes now operate across 164 countries and regions, and 23 units have joined this new alliance: 12 Confucius Institutes, 5 Chinese “host” universities, 2 foreign host universities, and 4 partner organisations and companies.

The alliance is pitched as a “Chinese + agriculture” (“中文+农业”) platform, promising an integrated system of courses, culture, platforms and training. The aim is to merge language, technology, culture and vocational skills, introduce China’s “advanced agricultural technologies” and poverty-reduction experience, and inject new momentum into global agricultural co-operation.

If the idea sounds abstract, there is at least one concrete precedent. Since 2012, Nanjing Agricultural University and Kenya’s Egerton University have run a Confucius Institute built around “Chinese + agriculture” vocational education, which is now presented as the template. On their joint initiative, Egerton’s Confucius Institute is taking the lead in the new alliance.

On the ground, this is likely to mean training programmes tied to local agricultural development plans, short courses in agronomy and agribusiness, and exchange platforms for “agricultural vocational and technical talent” (农业职业技术人才). For Confucius Institutes—often stereotyped as language, calligraphy and dumplings—this is a push to expand into technical training and rural development branding.

Hand-drawn Health Maps: One Village Doctor’s Attempts at Reform

In Zigui County, Hubei, a village doctor has gone back to basics—pen, paper, and an old motorbike—to do something that sounds suspiciously like public health.

Fifty-one-year-old Mei Chunlei (梅春雷) works as a village doctor in Qianjiangping Village, Shazhenxi Town, riding along steep mountain roads with a medicine box and a set of hand-drawn “health maps” (“健康地图”). Each of the village’s 383 households is marked with a number, and next to the names he adds simple red annotations: “老” (elderly), “高” (hypertension), “糖” (diabetes), and so on.

The maps grew out of frustration. Transferred into this mountainous village last year, Mei found himself lost—literally. He was not a local, the terrain was complicated, and house calls sometimes meant half an hour of backtracking on narrow roads. His wife’s offhand comment—“If only you had a map”—triggered the idea: visit every household, learn their health status, and sketch the geography as he went.

Two months of door-to-door visits later, 383 households, their locations and key conditions were all recorded across 12 hand-drawn sheets. When a villager’s son calls to say his 70-something mother is dizzy again, he unfolds the relevant map, locates the house, and rides straight there. In one recent case, he traced the dizziness not to untreated hypertension but to the opposite problem: the patient had doubled her dose of blood-pressure medication, overshooting into hypotension.

Now, according to Peoples Daily, chronic disease follow-up in Qianjiangping has “achieved full coverage”. Patients are seen roughly once a quarter, and those with unstable indicators are checked every couple of weeks. The article frames this as a model for changing the old mindset of “enduring small illnesses and dragging out big ones”(小病扛、大病挨).

In a health system often obsessed with large hospitals and big-ticket equipment, a village doctor’s sketch map is a reminder that sometimes the most useful information system is the one a single person can actually keep in their head—and on 12 carefully folded sheets of paper.

Modernising state-owned forest farms: policy from 2030 and 2035

China’s National Development and Reform Commission, together with the Ministry of Finance and others, has issued an Opinion on Accelerating the Construction of Modern State-owned Forest Farms (关于加快建设现代化国有林场的意见). The document sets out targets for 2030 and 2035, outlining what a modern state-owned forest farm is supposed to look like.

By 2030, the goal is to have a more complete management system, protected and restored ecosystems, and a basic mechanism for sustainable use of forest resources. Per-hectare forest stock volume is meant to rise by about 5%, and forest farms should become important growth points for the green development of forest regions and mountain areas. By 2035, the stock increase target is about 11%, with forest farms expected to form the backbone of ecological security, forest–grass industry development, and the supply of high-quality ecological products.

To get there, the Opinion calls for four main pushes:

– building a modern ecological protection system (现代化生态保护体系)

– developing modern characteristic industrial systems (现代化特色产业体系)

– upgrading modern technical equipment (现代化技术装备体系)

– and exploring modern management systems(现代化经营制度体系)

The repetition of “modern” is doing heavy rhetorical lifting. In practice, this likely means more zoning, stricter controls on logging, increased eco-compensation, and efforts to graft tourism, undergrowth economies, and forest-based industries onto what were once fairly narrow production units.

State-owned forest farms sit at an awkward intersection: part workplace, part community, part conservation area. If policy shifts succeed, they could become anchor institutions for mountain economies, with jobs in forest management, tourism, carbon projects and more. If they don’t, the risk is another round of paperwork-heavy “modernisation” that looks impressive in press briefings while the same ageing workforce patrols the same slopes with slightly newer tools.

Organic on the map: Qinghai’s grasslands under full monitoring

A recently released set of figures from Qinghai highlights how governance is becoming more data-driven, or at least more data-sounding. By the end of this year, the province expects to have organic monitoring in place across all usable grasslands, some 450 million mu (about 30 million hectares)—reportedly the first province in China to reach “full coverage”.

Officials frame this as part of a wider quality push: more green food, organic agricultural products and geographical indication products (地理标志农产品), more local standards, and more testing. The province now counts 1,337 certified items—double the 2021 figure—with 77 products listed in the national “famous, special, excellent, new” catalogue (全国名特优新农产品), and 24 national-level green-food raw material bases and organic production bases. A total of 318 firms are now classified as green/organic agri-businesses (绿色有机农牧业企业), with output officially valued at 16.227 billion yuan.

Behind the brand language is a thickening web of standards: over 800 local agricultural norms on the books, plus dedicated standard systems for yaks, highland barley, coldwater fish and other local specialities. Authorities say they’ve also tightened routine risk monitoring of “basket” products (菜篮子”产品)—vegetables, meat, eggs—targeting two batches of tests per thousand residents, with 2024 quality and safety pass rates at 99.6%, above the national average. Depending on your faith in statistics, that is either reassuring or ambitious.

In regions like Qinghai, where ecological civilisation (生态文明) narratives play a central political role, full-coverage monitoring serves several functions at once: it is a management tool, an enforcement mechanism for earlier grassland policies, and a way to underpin the expanding “green” brand on which local economies increasingly depend.

Guangdong’s late rice harvest and the machinery of food security

Further south, Guangdong is in the thick of its late-season rice harvest, and provincial media are making the most of the visuals: combines cutting through golden seas of grain, trucks waiting at the field edge, and driers humming as wet paddy arrives. All of this is framed within China’s broader food security agenda and the idea that the “rice bowl” must be firmly in Chinese hands.

From Guangzhou’s family farms to Shaoguan, Heyuan, Shanwei, Maoming, Zhaoqing, Jieyang, Yunfu and beyond, the coverage is similar: large, contiguous fields, high-yield varieties, and high levels of mechanisation. In Shaoguan’s Lechang, late rice harvest is reportedly more than 98% complete; in Haifeng County, 220,000 mu of late rice are being cut and rushed straight to drying facilities under a “grain doesn’t touch the ground” model (谷不落地). Demonstration plots in some counties report yields of around 950 jin of wet grain per mu.

Co-operatives and branded bases feature heavily. In Heyuan’s Zijin County, a co-op built around overseas Chinese families adopts a co-operative farmers model, has expanded from 123 to 218 mu, registered its own “Zirong Overseas Rice” brand, and expects late rice output of around 200,000 jin. Townships around the Pearl River Delta and western Guangdong stress “three increases” targets for grain—sowing area, yield per mu, and total output—backed by “good varieties + good methods + good services” (良种+良法+良服) packages.

In many ways, these stories are standard harvest propaganda in rural China: golden fields, busy machines, grateful farmers. But they also point to ongoing efforts to stabilise grain area, push up per-mu yields, and keep younger farmers and co-operatives invested in rice, even as labour costs rise and land competition intensifies. For a province often framed as purely industrial and export-driven, the message is simple: Guangdong still intends to carry its share of the national “rice bowl”—and to be seen doing so.