The Harvest: This Week in Rural China – Dispatch No. 12 (7 March 2025)

Navigating Shifting Policies: What This Week’s Announcements Mean for Rural China’s Future

Welcome to this week’s edition of The Harvest.

This week, we’ve seen a flurry of policy announcements, high-level meetings, and government activity that shed light on the future of China’s agricultural sector. It’s one of those weeks where the focus shifts from the broader landscape to the nuts and bolts of what’s happening in the halls of power.

In this dispatch:

China’s ambitious “Seven Zones and Twenty-three Belts” strategy to optimise agricultural productivity.

The Ministry of Agriculture’s efforts to address growing safety concerns in the agricultural sector

The push for more efficient, sustainable machinery on China’s farms.

A look at the awkwardly named “South Breeding Silicon Valley” project, an initiative to reduce China’s reliance on foreign seed suppliers.

Liaoning’s plan to become the world’s leading producer of edible mushrooms.

I always welcome your insights, as your feedback helps shape the direction of every dispatch. Please share your thoughts in the comments below or reach me at nathan@thisweekinruralchina.com.

As always, The Harvest remains free for all readers. If you find value in these dispatches and want to support the continued work behind them, consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support helps sustain this project and ensures we can continue publishing consistently:

Now, let’s dive into this week’s stories:

The “Seven Zones and Twenty-three Belts” Strategy

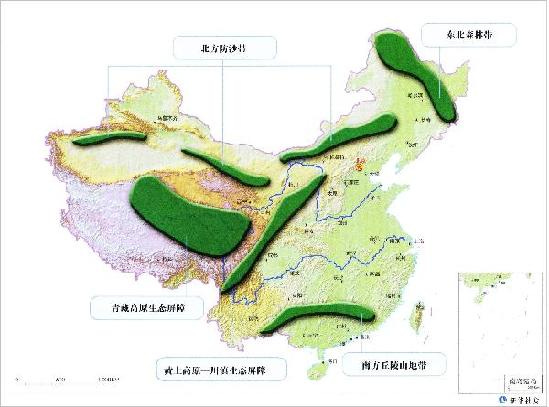

As we approach March and the spring planting season, China’s government is intensifying its focus on the “Seven Zones and Twenty-three Belts” (七区二十三带) strategy, a cornerstone of the country’s agricultural development. Central to the Rural Revitalisation Plan (乡村全面振兴规划), this initiative is designed to fortify agricultural production across China while ensuring national food security. It is an ambitious step towards shaping China’s goal to be a global leader in sustainable, high-output farming.

The “Seven Zones and Twenty-three Belts” strategy divides China’s vast agricultural landscape into seven key zones, each selected for its ecological and climatic strengths. Twenty-three industry belts complement these zones, each specialising in distinct agricultural products, creating a diverse and robust food production system capable of meeting both domestic and global demand.

For instance, the Northeast Plain, famed for its fertile soil and large-scale mechanisation, is home to the rice belt, renowned for its high-quality Japonica rice. The region excels in cultivating rice, maize, soybeans, and livestock, making it one of China’s most important agricultural hubs. Similarly, the Huang-Huai-Hai Plain, stretching across Shandong and northern Henan, focuses on wheat production, a staple crop in China’s diet.

Moving south, the Yangtze River Basin is critical for producing rice and other crops, thanks to its ample water supply and temperate climate. Further to the west, the Fenwei Plain produces high yields of wheat and potatoes, while the Hetao Irrigation Area is known for its high-efficiency cotton farming, crucial for the textile industry. In the southern regions, the agricultural focus shifts to tropical fruits, tea, and rubber in places like South China, while Gansu-Xinjiang specialises in wheat, cotton, and other arid-zone crops, capitalising on irrigation technologies in the region’s expansive, dry plains.

This strategic division is underpinned by the National Spatial Planning for Land Development (全国国土空间开发规划), which optimises land use based on each region’s natural advantages. Aiming to balance agricultural output with ecological sustainability, this framework ensures that each zone reaches its full potential while preserving environmental integrity.

Academics have hailed the “Seven Zones and Twenty-three Belts” initiative for its potential to streamline agricultural resources and increase efficiency across the board. Professor Jiang Heping from the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences explains, “This strategy maximises resource allocation, ensuring each region produces what it does best. In doing so, it eliminates inefficiencies that arise from poorly planned agricultural layouts.”

Professor Huo Xuexi from Northwest A&F University agrees that a more coordinated approach to food security remains crucial despite China’s recent grain production progress. “Given the complexities of global food markets, we need long-term, strategic investments in agricultural infrastructure,” he says. “The creation of these ‘food security industry belts’ is a direct response to the growing challenges of stabilising grain production in an evolving world.”

With the “Seven Zones and Twenty-three Belts” strategy, China is positioning itself to optimise agricultural productivity and meet the demands of modern society. By integrating cutting-edge technology with traditional farming methods, the country aims to secure its food supply and create a prosperous, sustainable agricultural system. Ultimately, the vision is to build a resilient farming landscape that benefits the nation’s farmers and consumers.

Agricultural Safety in China: A Growing Priority

This week, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) held an annual meeting focused on agricultural safety in China, discussing strategies for 2025 and highlighting progress made in the past year. The meeting, which took place on 3 March in Beijing, highlighted the importance of adhering to safety standards within the agricultural sector, in line with directives from President Xi Jinping.

The agricultural sector in China, employing over 270 million people, is one of the largest in the world but remains plagued by persistent safety risks. Official data from MARA indicates that agricultural accidents are a leading cause of fatalities among rural workers, with over 17,000 deaths recorded annually. This equates to approximately 6.3 deaths per 100,000 rural workers—a figure that appears high compared to international standards. Despite frequent suppression of such statistics by local and central authorities, the data highlights an urgent need for stricter safety protocols and improved regulations.

In neighbouring India, which also has a large agricultural workforce, annual fatalities are around 10,000. However, India’s much larger population skews direct comparisons. When adjusted, the fatality rate stands at roughly 0.7 deaths per 100,000 people—significantly lower than China’s. The rate is even lower in the United States, where agriculture is highly mechanised, and safety regulations are more stringent, at approximately 0.3 per 100,000 workers.

Critics question the accuracy and transparency of MARA’s figures, with some arguing that the actual death toll could be even higher. Underreporting is a known issue, particularly in remote rural areas where many incidents go undocumented. Additionally, MARA’s reports tend to emphasise large-scale accidents, often overlooking smaller yet frequent incidents that contribute to overall risk.

The Ministry’s latest meeting included discussions on the “Three-Year Action Plan for Agricultural Safety Production” (安全生产治本攻坚三年行动), which aims to tackle both immediate risks and long-term structural issues within the sector. The plan is a response to a significant number of accidents arising from inadequate safety equipment, poor working conditions, and a lack of sufficient safety training for agricultural workers. A 2024 report from the China National Safety Production Administration indicated that over 40% of agricultural fatalities were caused by machinery-related accidents, with many workers failing to use basic protective equipment.

MARA’s action plan outlines several key measures for improvement, such as better enforcement of safety laws, adopting advanced farming technologies to reduce manual labour, and a national safety education campaign targeted at farmers. It also focuses on strengthening monitoring and risk assessment, ensuring that safety regulations are followed at all agricultural production levels, from small-scale farms to larger, mechanised operations.

While the government’s efforts are commendable, challenges remain. Rural areas still struggle with limited access to healthcare, poor infrastructure, and a shortage of skilled safety inspectors. Moreover, many smaller farms, where most of China’s agricultural workers are employed, do not have the resources to implement ‘high-tech’ safety measures. As China works toward an agricultural “safety net,” it must balance innovation with accessibility to ensure that safety improvements reach those most at risk in the countryside.

China’s “South Breeding Silicon Valley”: The Grand Plan to Secure Food Independence

On 28 February 2025, China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs (MARA) convened in Sanya, Hainan, to assess the progress of its ambitious “South Breeding Silicon Valley” (南繁硅谷) project. Launched in 2023, the initiative is central to Beijing’s push for agricultural self-sufficiency, aiming to reduce dependence on foreign seed technology and enhance food security for its 1.4 billion people. However, the reality is more complicated, raising important questions about whether these efforts will be enough to secure true independence in feeding China’s population.

Hainan’s tropical climate supports year-round seed breeding, accelerating research and development. Billions of yuan have been invested in state-of-the-art labs and genetic modification programs. Yet, while China has made progress in hybrid rice, it still lags behind Western firms in gene editing and crop trait selection. Intellectual property restrictions on genetically modified seeds, controlled by U.S. and European agribusiness giants, remain a significant hurdle.

Climate change adds another challenge. Erratic weather patterns—droughts, floods, and extreme heat—threaten crop yields, raising doubts about whether advanced breeding alone can ensure China’s food security. Furthermore, while Hainan’s high-tech labs innovate, farmers in China’s interior still rely on outdated methods, revealing a gap between innovation and practical application.

The global implications of China’s seed push are profound. By reducing reliance on imports, Beijing is insulating itself from potential U.S. sanctions targeting agriculture. However, complete self-sufficiency remains elusive, especially for high-yield GM crops restricted by Chinese regulations. Meanwhile, China’s aggressive investment in seed technology has sparked concerns over intellectual property rights, with past accusations of agricultural espionage casting a shadow over its efforts.

The South Breeding Silicon Valley is an ambitious attempt to secure China’s food future, but technological, environmental, and geopolitical obstacles persist. Its success will depend not just on investment and policy, but on overcoming deep structural challenges that no government rhetoric can erase.Liaoning Province is aiming to create a world-class edible mushroom industry by 2027. Known for its rich agricultural history, Liaoning has already become one of the country's top producers of various mushroom species, including shiitake, enoki, and black fungus.

In 2023, Liaoning produced 1.33 million tonnes of edible mushrooms, accounting for 3.1% of China’s national total, valued at 8.7 billion RMB. The province’s success in mushroom farming is largely driven by its favourable geography and climate, with key production areas in the eastern mountainous regions, including Shenyang, Anshan, and Chaoyang. This output places Liaoning among the top producers, with a growth target of 1.5 million tonnes by 2027, highlighting the province’s increasing contribution to the national mushroom industry.

To capitalise on this momentum, the provincial government has launched the “Liaoning Provincial Edible Mushroom Industry High-Quality Development Plan (2025–2027)” (辽宁省食用菌特色产业高质量发展工作方案). This plan aims to elevate the industry, with goals to reach 1.5 million tonnes annually and an industry chain value exceeding 12 billion RMB by 2027.

The plan includes key objectives such as upgrading production facilities to be more mechanised and intelligent, expanding deep processing capabilities, and improving logistics and circulation systems. Additionally, the province will strengthen its brand recognition, develop standardised production areas, and establish five high-standard production hubs and ten demonstration towns by 2027.

A major focus is also on stimulating rural economic growth through new agricultural business models that involve village collectives and larger enterprises. These efforts aim to increase farmers' incomes, improve infrastructure, and ensure long-term, sustainable growth for the edible mushroom industry.

As one of China’s major mushroom-producing regions, Liaoning is poised to play a pivotal role in shaping the future of the country’s edible mushroom industry. With strategic policies and a focus on modernisation, the province is set to lead the sector to new levels of success by 2027.

Liaoning Aims to Build China’s Leading Edible Mushroom Industry

Liaoning Province, is setting its sights on creating a world-class edible mushroom industry by 2027. Known for its rich agricultural history, Liaoning has already established itself as one of the country’s leading producers of various mushroom species, including shiitake, enoki, and black fungus.

In 2023, Liaoning’s edible mushroom output reached 1.33 million tonnes, accounting for 3.1% of the national total and estimated at 8.7 billion RMB. The province’s success in mushroom farming is driven by its favourable geography and climate, with key production areas in the eastern mountainous regions, including Shenyang, Anshan, and Chaoyang.

To capitalise on this, the provincial government has unveiled an ambitious development plan to elevate the industry to new heights. The “Liaoning Provincial Edible Mushroom Industry High-Quality Development Plan (2025—2027)” (辽宁省食用菌特色产业高质量发展工作方案) outlines a target of 1.5 million tonnes of mushrooms produced annually and an industry chain value exceeding 12 billion RMB by 2027.

The plan emphasises key objectives, such as upgrading production facilities to be more mechanised and intelligent, expanding deep processing capabilities, and improving circulation and logistics systems. Additionally, Liaoning will focus on strengthening its brand recognition, developing standardised production areas, and establishing five high-standard production hubs and 10 demonstration towns by 2027.

The provincial government also seeks to foster rural economic growth by encouraging new agricultural business models involving village collectives and larger enterprises. This approach aims to increase farmers’ incomes, improve rural infrastructure, and create sustainable, long-term growth for the edible mushroom sector.

As one of China’s major mushroom-producing regions, Liaoning is poised to play a pivotal role in shaping the country’s edible mushroom industry. With the support of strategic policies and a focus on modernisation, the province is determined to lead the sector to new levels of success by 2027.

Between Mountains and Waters - Photo of the Week for 7 March 2025

Captured in Zhada County, Ali, Tibet, this breathtaking winter scene reveals the Zhada Earth Forest, a unique geological formation where eroded sandstone pillars rise from the ground, resembling a forest of towering rock ‘trees.’ Blanketed in fresh snow, the landscape transforms into a silver wonderland, showcasing the raw beauty of the Tibetan plateau. This remote corner of China, sculpted by wind and water over thousands of years, serves as a stunning reminder of nature’s grandeur, far from the reach of modern civilization.

Credit: Cui Huayang / People’s Picture Network (via People’s Daily)