Reflection III: Passing the Torch – How Wu Wenguang’s Filmmaking Transformed My Understanding of China

How One Filmmaker Removed His Own Voice, Allowing Me to See the Complexity of China

Bumming Through Beijing – Finding Wu Wenguang

Back when I was a postgraduate student in Edinburgh, drowning in deadlines and instant noodles, I’d stay up far too late, scouring the internet for something real. Between flashcards full of Chinese vocabulary and academic texts that talked more about policy than people, I craved something that cut through the noise. I wasn’t interested in the sanitised version of China—travel writing, state media, Western think tanks. I wanted the cracks. The voices no one was meant to hear.

Then I stumbled across Bumming in Beijing (1990). It was a total fluke. Just a rough, glitchy copy buried in the weeds of some obscure torrent site I probably shouldn’t have been on. It was past midnight—one of those nights where sleep felt dishonest, and I was too wired to pretend otherwise. And the film… it hit me. Not like inspiration—more like recognition. Wu Wenguang’s first feature didn’t try to impress. It didn’t care if you watched. It just was. A handful of artists and drifters squatting in post-Tiananmen Beijing, scraping by, saying no to everything highly conventional Chinese society expected of them. No narration. No arc. Just fragments. Unsmoothed. Unapologetic. It felt like stumbling into someone’s memory—uncut and unfinished—and not being sure if you were allowed to be there. But I kept watching.

Wu didn’t explain them. Didn’t dress their lives up in political soundbites. He simply let the camera roll—and that silence, that absence of commentary, was exactly what made it powerful. He gave the space back to the people. That idea—of stepping aside so others could speak—stuck with me.

Fuck Cinema (1993) hit even harder. The title alone was enough to stop you in your tracks—blunt, pissed off, done with it all. But it wasn’t just a rant against the film industry. It was a question, hidden in plain sight: Who gets to dream? The film follows a man from the countryside, living rough on Beijing rooftops, desperately trying to get his script made. No connections. No money. Just the raw need to tell a story—and a world that keeps slamming doors in his face. That’s when it clicked: Wu had already shifted his gaze. This wasn’t just anti-establishment; it was anti-elitism. Anti-gatekeeping. The subject of Fuck Cinema wasn’t some polished dissident—he was one of the millions China’s miracle had teased, but left behind.

Watching it, I started to realise that a good documentary isn’t just about capturing truth—it’s about deciding whose truth gets seen. Who gets the microphone. And sometimes, the most radical thing a filmmaker can do is step back and listen. No fixing. No narrative arc. Just bearing witness, even when there’s no payoff.

By the time At Home in the World (1997) came along, that shift had deepened. Wu wasn’t filming rebels or artists anymore. He was listening to farmers, migrants, and people floating through the cracks of Chinese society. And he treated them with care—no spectacle, no saviour complex. Just stillness. Silence. Space. That film taught me something no lecture ever could: Stories don’t need to shout to matter. Sometimes, the power’s in the pause. The refusal to explain. The quiet act of staying with someone long enough for their truth to unfold.

Then came Jiang Hu: Life on the Road (2000), and something broke open in me. It followed wandering performers—people scraping by, doing backflips for pocket change, living on the very edge. Wu didn’t frame them as victims or heroes. He simply let their dignity shine through the dust. That’s the power of his work—it never begs for sympathy. It asks only that you look closely and without judgment.

The biggest shift came with The Memory Project (2006). By this point, Wu had taken his hands off the wheel. He wasn’t directing anymore—he was handing out cameras. Training rural villagers—survivors of the Great Famine—to tell their own stories. No middleman. No filter. Just raw testimony. This wasn’t just film—it was memory at work. History from the ground up in a country where silence is often policy.

“Here’s a camera,” he said. “Tell the world what it’s like to be you.”

Filming the Forgotten – Wu Wenguang and the People’s Archive of China’s Vanishing Villages

Wu never set out to become an archivist in forgotten China. He simply refused to look away. When he launched the Village Documentary Project in 2005, it was a declaration of his retreat from filmmaking—no fanfare, no speeches. Just: give people the tools, then step aside.

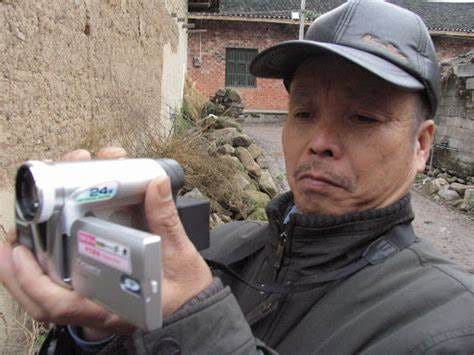

At his Caochangdi Workstation in Beijing, Wu handed cameras to farmers, grandparents, children. He didn’t just teach them to film the predictable—festivals, rice planting—but also the uncomfortable: funerals, arguments, abandoned schools, families torn apart. These are the kinds of stories the state media would rather bury, either because they lack mass appeal or because they bordered on controversy.

The result? Not polished cinema. No sweeping shots or glossy edits. Just shaky footage. Awkward silences. People forgetting they’re on camera. But it’s raw. These films feel like sitting in someone’s living room, watching them unravel decades of unspoken truths—every word heavy with things that could never be said aloud.

And Wu? He pulled back. Where most filmmakers would have tightened their grip, he let go. That is his genius. He didn’t want to be the voice of the voiceless—he handed them the microphone and disappeared. His subjects became filmmakers and storytellers. Historians of their own lives. What had begun as Wu’s project had stopped being about him—it became a stubborn authenticity.

These films weren’t made for Instagram clips or Netflix. They’re slow, patient, and often mundane. But that’s rural China—where nothing happens for weeks, and then, in an instant, everything changes. The Village Documentary Project feels like the land it documents: weathered, fractured, ghostly, gritty.

Wu Wenguang’s films didn’t just change the landscape of documentary filmmaking—they changed me. It was all in the seeds he planted: the cameras in calloused hands, telling stories no one had bothered to ask. As I sat with his work, something shifted. I began to see China again—not the sanitised version I’d studied in textbooks or heard about in lectures—but the real, messy, lived history I saw when I was living in rural China.

As I continued my studies and returned to China, Wu Wenguang’s work stayed with me. It taught me that China isn’t something that can be neatly packaged, and no amount of theorising in academic essays could distil it into a single truth. I began to realise that there are many versions of the truth. That China, vast and complex, is full of lies, deceptions, and countless valid versions of truth. These truths are found in the everyday—the forgotten corners, the unlikely places, the quiet moments, the bulldozed rubble, and the turning of the soil.

And so, with every step forward, I still carry his archive with me—tucked into the folds of my own journey, a reminder that the truth of China, like all truths, lies not in the grand narratives but in the quiet, unspoken stories waiting to be uncovered.

Thank you Nathan. This is a fantastic, powerful article.

The only thing I have to say is that in the photo "Wu Wenguang instructing villagers at his Caochangdi Workstation", the people learning to use the cameras appear to be all men. Do you know if any women were actually involved in his "give the people a camera" project, or was it limited to 'give men a camera'? Having said that, it's still a powerful thing he has done. I love your descriptions about the films being just like rural China, "slow, patient, and mundane, where nothing happens for weeks, and then, in an instant, everything changes".